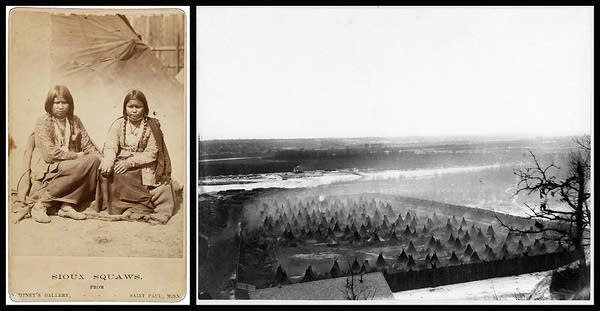

In the aftermath of the U.S.-Dakota war in 1862, Congress passed a law that banished the Dakota people from their homelands in Minnesota. It’s a law that remains on the books to this day.

In February of 1863, Congress annulled all treaties between the Dakota tribes and directed any money owed to them be paid to white settlers that were harmed during the war. The following month, acting under pressure, they passed another act that forced the removal of the Sisseton, Wahpeton, Medawakanton and Wahpakoota bands of Dakota people to North Dakota, South Dakota and Nebraska from Minnesota. Descendents of those removed still live there today and are living under this same law — until last month.

South Dakota state Sen. Tamara Grove sponsored the bill to repeal the act. It passed 32-3.

Grove said the bill came out of a meeting she and leaders of tribal nations had in South Dakota. The meeting in January was meant to be a reset after former Gov. Kristi Noem left to lead the Department of Homeland Security under President Donald Trump. Over the last couple of years, Noem had called for an audit of the tribes and claimed they were harboring leaders of drug cartels — something tribal leaders strongly disputed.

Grove said she spoke with the leader of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate, Chairman J. Garrett Renville, who brought up the many times any attempt to repeal the act did not make it through South Dakota’s Legislature. She said even though the act isn’t enforced and is obscure, it’s still harmful.

“Today, let’s reset. Today, let’s rebuild. Today, let’s start to listen and actually hear,” Renville said at the Jan. 15 State of the Tribes address.

Grove said the 1863 law has the potential to be weaponized. For example, if a tribal citizen were arrested, pulled over by law enforcement or caught up in the criminal justice system, the removal act — even though it is more than 150 years old — could be used against them.

“It just takes … one person. And will that person exist? I don’t know,” Grove said.

“It’s not really something that I would want for my family, for my children, like they could literally point at that and a judge, the judge’s job is not to fix the law, they would have to interpret the law. And so for my family, and for you know, all of our families here in South Dakota… let’s repeal it.”

A similar bill was introduced by former Minnesota Rep. Dean Urdahl in 2009. It passed in May that year and was signed by former Gov. Mark Dayton. Urdahl, a Republican from Grove City, said the bill was largely symbolic but was important to Minnesota tribal nations.

The act, SR702, acknowledges it remains a federal law despite it not being enforced. South Dakota’s bill now heads to President Trump’s desk with a request for a statement of reconciliation. Grove said she is confident the South Dakota delegation will get it to the president’s desk and that he will sign it. Grove served on Trump’s 2016 diversity commission.

Iyekiyapiwiƞ Darlene St. Clair said it isn’t clear to her what the act would actually do.

St. Clair is an Indigenous Research Professor whose work focuses on Dakota studies and Native Nations.

“It seems like it doesn't really do anything for Dakota people,” St. Clair said.

“Any questions we might have about treaty obligations… there’s a lot that at least I don’t understand, or it’s not included in the legislation.”

St. Clair said what is missing in the bill is any act of reparations or any apology, or any discussion among Dakota people living across Minnesota and Canada.

“I think that the Dakota tribal governments, both in the U.S. and Canada, would probably need to have a stronger conversation about what would the removal of this exile order do for Dakota people, what do we want it to do? And I don't think that that conversation has really taken place,” she said.

The act to repeal the banishment of Dakota people from their homeland doesn’t include language offering an apology or any reparations.

Grove told MPR News that language about reconciliation and reparations was taken out of the language of the bill.

“We took out all teeth,” Grove said. She said a few years back, tribal nations in Minnesota came to South Dakota when a similar bill was being debated upon and wanted reparations.

“That really just shut everything down. As far as we’re concerned, what the tribes wanted was just ‘get this thing repealed, get that off the books.’”

In 2020, the House State Affairs Committee voted 8-5 to kill a similar bill that would have repealed the Dakota Removal Act.

MPR News reached out to the Minnesota Indian Affairs Council seeking a comment on this issue and was provided a written statement via email.

“MIAC does not provide comments on matters related to other states or jurisdictions. Thank you for reaching out, but please note that we do not represent the tribes in this regard,” wrote communications manager Michele Poitra.

“I am in support of an accounting, a true accounting, of ethnic cleansing and genocidal practices against Dakota people. I think my concern is, I feel like this legislation does not do much to get us there,” said St. Clair.

Collected from Minnesota Public Radio News. View original source here.

Minnesota Public Radio (MPR) is a public radio network for the state of Minnesota. With its three services, News & Information, YourClassical MPR and The Current, MPR operates a 46-station regional radio network in the upper Midwest.

Last updated from

Minnesota Public Radio (MPR) is a public radio network for the state of Minnesota. With its three services, News & Information, YourClassical MPR and The Current, MPR operates a 46-station regional radio network in the upper Midwest.

Last updated from